In the past two years we have witnessed an unparalleled disaster, and not merely in terms of the futures ruined or the lives cut short. Our planet, from the richest country to the poorest, also suffered through a dramatic crisis of equipment. With wards overwhelmed by Covid-19 patients, the everyday paraphernalia of countless hospitals were suddenly in short supply. The results, moreover, were told in articles and news clips the world over. In the Italian town of Bergamo, for instance, elderly patients died in corridors for lack of beds. At Huesca, in Spain, nurses posed for photos decked out in robes made from rubbish bags and masks loaned from a private firm nearby. Across the Atlantic, in America, the second half of 2020 saw over 30% of office-based doctors endure a shortage of PPE equipment.

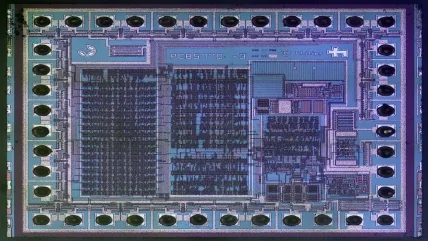

Thankfully, this dearth of basic kit has gradually abated over the past year. But if experts in the US government are to be believed, the medical device sector may soon be facing an even bigger threat: a lack of semiconductors. Sometimes dismissed as the purview of nerds and their smartphones, these chips are in fact instrumental in powering countless medical machines, from ultrasound devices to ventilators. If their supply was to run out, these machines, and many others, would be impossible to build. Given there are an estimated 160,000 ventilators in the US alone, it goes without saying that such a situation could certainly presage a medical catastrophe.

Not that industry insiders have been unmoved by the apparent emergency. Indeed, there’s now talk of a fully-fledged ‘industrial strategy’ for semiconductor production, involving the full might of the American government. Yet if supply chain and manufacturing problems have undoubtedly caused a lag in semiconductor availability, overcorrection is a danger too. Given the likely trajectory of chip production, in fact, the United States is arguably in a far stronger position than its Chinese rival. And given our world’s ominous geopolitical instability, some experts even worry that intensive action to fix the semiconductor shortage could actually make the situation worse – with untold consequences for medical devices alongside every other industry.

Chips in a storm

It’s difficult to overstate how vital semiconductors are to the medical device industry. If nothing else, this is reflected by the headline numbers. Though it only represents a fraction of overall semiconductor demand, after all, the therapeutic market for chips was worth $5.1bn in 2019, and is expected to enjoy a CAGR of 10.2% between 2021-6. According to another recent study by the Advanced Medical Technology Association, two-thirds of medical device firms claimed to use semiconductors in at least 50% of their products. That figure certainly seems accurate if you focus on specific conditions. As the World Health Organisation (WHO) emphasises, for instance, over 400 million people now suffer from diabetes worldwide, leading to a sharp rise in the need for glucometer chips. Another example comes from the field of psychological disorders. And now that illnesses like schizophrenia can be partially treated with integrated circuits, the need for semiconductors is increasing here too.

And as Robert Lewis says, this need has only become more frantic since the pandemic. “I’m sure the US especially, and the EU, had a panic moment when they realised that a lot of what we might call ‘pandemic response’ had been outsourced.” In other words, suggests the senior international consultant at Chance Bridge Partners, a Chinese law firm, the rush to secure medical kit focused Western minds when it came to semiconductors too.

“I’m sure the US especially, and the EU, had a panic moment when they realised that a lot of what we might call ‘pandemic response’ had been outsourced.”

Robert Lewis

4/5

The proportion of the current chip production that sits across the Pacific.

Deloitte

This concern is totally justified – up to a point anyway. In April 2020, for instance, ventilator manufacturers announced shortages of key semiconductor components, totalling over nine million parts. National governments began making similar noises, with the UK’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport recently announcing an investigation of the country’s semiconductor needs.

Naturally, all this begs the question: how do we explain the shortage? As Lewis’s comment implies, part of the answer lies in outsourcing. Taiwan and South Korea have long dominated chip manufacturing, the two East Asian countries together controlling 81% of the global market. With the pandemic supercharging demand, and lockdowns disrupting production lines, it was perhaps inevitable that chip availability would be squeezed. It hardly helped that accidents hampered production even further, notably via a fire at one of Japan’s largest chip factories. But events like that are overshadowed by broader supply chain issues. Between congested ports and a lack of lorry drivers, delivery times have reached record highs on both sides of the Atlantic.

“You’re always going to have people who take every issue and want to frame it in terms of criticising political opponents – so a lot of government action is to forestall or preclude that type of criticism.”

Robert Lewis

Sharing the supply chain

In June 2021, the US Senate showed that bipartisanship wasn’t quite dead, and passed the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act by a majority of 36. Thankfully known as the CHIPS Act for short, the legislation promises, according to the US commerce secretary, to “revitalise” the US semiconductor industry in a dangerous world. Perhaps more remarkable than the ends, however, are the CHIPS Act’s means. Abandoning America’s long tradition of free market enterprise, the law mandates $50bn in state subsidies for domestic semiconductor investment. In practice, that encompasses the creation of a National Semiconductor Technology Centre, as well as research into new technology. Nor is Capitol Hill alone. In Europe, Italy, France and a number of other EU countries plan to jointly pump $145bn into the continent’s own chip manufacturing capabilities.

To a certain extent, Lewis understands this approach, emphasising that onshoring essential chip production is widely seen as a “national security issue.” Given how crucial chips are to medical manufacturing – let alone a raft of other industries – why wouldn’t governments want to nationalise them? For Lewis, an answer begins with pure pragmatism. As he points out, the passing of the CHIPS Act caused America’s rivals in Beijing to strike back, hoarding Chinese chips and exacerbating the shortage. More fundamentally, Lewis wonders whether the dash to shore up domestic production is missing the point. “You have the US panicking that it doesn’t control the whole supply chain,” he says. “But actually, it pretty much does.” A fair point. Over four-fifths of current chip production may sit across the Pacific, after all, but both South Korea and Taiwan are stalwarts of the Western alliance. And even if the People’s Liberation Army occupies Taipei tomorrow (a remote possibility given events in Ukraine), America’s mega corps could soon take up the slack. According to one report, private firms like Nvidia and IBM plan $834bn in new chip capacity over the next decade, easily dwarfing the $50bn offered by Congress.

Lewis argues that leaving investment to eager capitalists makes more sense in other ways too. “Politicians tend to be too late about understanding what’s important, and tend to be subjected to lobbying by people who don’t put their own money at risk,” he says in a critique of the statist approach. When it comes to medical devices in particular, meanwhile, it’s also important to appreciate what kinds of semiconductors machines actually need. So-called ‘standard’ semiconductors – off-the-shelf and mass-produced – may be less customisable than their more specialised cousins. But they’re also quicker to make and get to market.

And as it happens, many common medical devices use precisely these chips, from ultrasounds and CT scanners to MRI machines. To put it another way, there’s some evidence that if manufacturers design products with the future in mind, they can act to avoid the worst shortages until the market finally stabilises.

Getting their act together?

What, then, does the future hold for the semiconductor industry? Though Lewis is reluctant to make watertight predictions, he suggests that rising geopolitical tensions could yet push politicians to promote schemes like the CHIPS Act – regardless of their efficacy in the real world. “In my view, it’s politicians needing to show that they’re doing something,” he says. “You’re always going to have people who take every issue and want to frame it in terms of criticising political opponents – so a lot of government action is to forestall or preclude that type of criticism.” That, at any rate, seems to be happening rhetorically. As President Biden recently warned colleagues in the House unwilling to pass the CHIPS Act: “All [semiconductor manufacturers are] waiting for is for you to pass this bill.”

What all this means for medical devices in particular remains unclear. Lewis, for his part, doesn’t expect any funding to be ring fenced for hospital machines or any other area, arguing that any approach will inevitably be “holistic.” What that means for the availability of glucometer chips and the like remains unclear – but there are signs the current crisis may be coming to an end. According to Pat Gelsinger, CEO at Intel, the current chip shortage will continue through 2023. By then, of course, new hiccups might have disrupted supply chains once more – whether due to government action, or thanks to some other emergency. Given the way our century is going, that, at least, should come as no surprise.

81%

Taiwan and South Korea control the majority of the chip manufacturing market worldwide.

CNBC

$834bn

Private firms like Nvidia and IBM plan this amount in new chip capacity over the next decade, dwarfing the $50bn offered by Congress.

Lexology