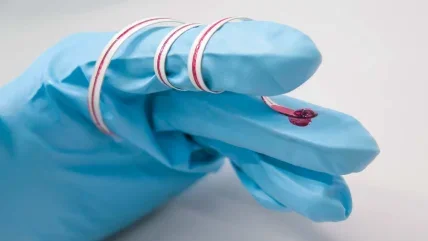

“This is my universe,” says Bruce Tromberg. He is sat in front of a cabinet filled with books at his home office in Maryland. In front of him, spread out on his desk, is an array of the latest Covid-19 tests, many of which are still in the final stages of development. He picks up a slim rectangle of clear plastic, perforated with 96 identical tiny holes. In a single day, this integrated fluidics chip has the capacity to process a staggering 6,000 tests. Next to it is a portable lateral flow test, no bigger than a memory stick. At one end is a circular pod for collecting saliva samples. Designed for accessibility, the test gives results within minutes.

A 30-year technology development veteran, Tromberg is currently leading the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RadX) innovation programme. The initiative is providing researchers across the US with $500m of funding to speed up Covid-19 test development. It was launched in April 2020, just days after Congress provided the US National Institutes of Health with an emergency supplemental appropriation of $1.5bn to dramatically increase testing capacity and make six million daily tests available to the US public before the end of the year. At the time, only a few thousand tests were being carried out per day. Tromberg highlights the disparity between what manufacturers were able to achieve and the sheer scale of testing required. “That’s where RadX comes in,” he says, “to fill that gap.”

Pressure to perform

The pressure to accelerate development and meet the urgent demand for Covid- 19 testing has sparked concerns over accuracy globally. Most strikingly, in March, the Spanish Government was forced to withdraw 58,000 Chinesemade testing kits after it emerged they had an accurate detection rate of 30%.

RadX has a stringent evaluation process in place to minimise the risk of such poor-quality tests reaching the public. From the completed applications, the most promising tests are put through an intense one-week ‘shark tank’ process, during which a team of experts compile a detailed review examining the clinical, technical and commercial strengths and weaknesses of the proposed test to decide whether an investment should be made. If a project successfully makes it through, clinical testing and scale-up manufacturing begins. This approach compresses the usually lengthy process of bringing a product to market – which can take years – to a matter of months. “Usually delays are related to ambiguities in the market,” explains Tromberg. “The unique thing here is there are no ambiguities. We’ve got a market: we need to deliver millions of tests per day.”

Also committed to assessing the deluge of Covid-19 tests is Rangarajan Sampath, chief scientific officer at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND). The global nonprofit has been driving innovation in the development and delivery of diagnostics in the world’s poorest countries for nearly 20 years. Things are no different with Covid-19. As the scale of the pandemic became clear, Sampath and his colleagues began to think about how FIND could best position itself to help. They decided to test the tests. “We didn’t need to jump into the fray to support companies in early development because that was already being done,” he explains. “Where we felt we could bring the best value to the global community was by doing independent evaluations, looking at the tests from an objective perspective to see how well they actually perform.”

$500m

RadX programme funding for the development of Covid-19 tests.

RadX

FIND collaborated with WHO to develop a set of protocols to carry out standardised testing. In mid- January 2020 they put out a call to manufacturers to submit their tests for evaluation. By late February, over 500 proposals had been submitted. One of the main goals is to be able to supply information about the accuracy of the tests to large-volume procurers like the Global Fund, which distributes millions of tests to low and middleincome countries. As FIND does not have the time or resources to evaluate every test, it prioritises those with clear commercial capabilities, assessing their performance and ease of use along with a range of other factors that could determine their success in the marketplace.

Evaluating thousands of Covid-19 samples is no easy task. Human error in taking swabs, how the sample is stored and the length of time between the sample being frozen and used can all affect the performance of a test. FIND is evaluating both molecular – or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) – tests, which detect the genetic sequence of the virus, and antigen tests, which detect the presence of its unique protein structures. “Molecular tests are somewhat easier to develop in the early phase as, once you know the sequence, the method of analysing them is fairly standard, and they perform reasonably well,” explains Sampath. “The challenge with the antigen test is that the sensitivity is not as good. They work well when the viral load is high, but if you miss the three-to-five-day window, the antigens could rapidly drop. If you don’t know exactly when the infection was, you may end up with a false negative.”

Population differences

As Tromberg is quick to emphasise, “No test is perfect – it’s mathematically impossible.” However, it’s vital to understand the population being tested in order to determine the types of error that can be tolerated. “If you have a vulnerable population that is very high risk, such as people with underlying conditions at an advanced age, the test [you use] should be the most rigorous with the highest sensitivity because the risk of not getting it right is too high,” he explains.

“At the other extreme, let’s say I’m a 21-year-old soldier on a troop ship and the virus is definitely on board. I’d want to get tested as fast as possible, like with one of these,” Tromberg continues, holding up the portable lateral flow test. “It might not be the most accurate test but if it’s wrong it’s not that bad because it’s not a super high-risk population group.” This is an issue Tromberg and his colleagues are keen to learn more about. “The crazy thing about this virus is that some people don’t have any symptoms while others end up in desperate shape on a ventilator,” he says. “The big mystery is how you will respond to the virus.” RadX Underserved Populations is a division of the main programme, which aims to find out just that by improving access to testing for underserved and vulnerable populations, and working to understand more about the factors that lead to the virus placing a disproportionate burden on particular groups. Part of the strategy involves investing in new technologies that can help predict how sick people will get and how they are likely to respond to new therapies.

58,000

Inaccurate Covid-19 tests withdrawn by the Spanish government in March.

Government of Spain

Balancing act

In the US, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) emergency use authorisations (EUAs) have fasttracked the development of several diagnostic tests, triggering accusations from leading scientists that inaccurate tests are flooding the market. “It’s the wild west out there,” epidemiologist Michael Osterholm told National Geographic in May. Shortly after preliminary findings from a House Oversight and Reform Subcommittee revealed that companies were taking advantage of the temporary relaxation of regulations to market fraudulent antibody tests, the FDA announced it would be toughening up its EUA requirements.

“We’re right in the middle of a pandemic, and regulations are the exact opposite of the fast response that is needed,” says Sampath. “In a way, the two are always going to conflict.” He goes on to explain that once the sequence of the virus was established, it became much easier to follow a standard template to evaluate molecular assays. The biggest challenge came with assessing antibody tests, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic when little was known about the length of time different antibodies remain detectable after infection. On top of this, crucial factors like the context in which the tests were being used were not properly examined. This is hardly surprising, he says, given that “it was looking pretty apocalyptic in Europe in February and March, so there was big political pressure to speed things up”.

While some antibody tests seemed to be performing well in small localised areas in China where the prevalence of the virus was high, they failed to reach the same standards when they were carried out on large populations in Europe. As a result, following a month of hype, the perceived value of antibody tests dropped significantly. Despite this, Sampath stresses that they still have a role to play. “Everyone was trying to fight the fire with whatever tools they had, doing the best they could but without all of the information needed,” he explains. “The victim was the antibody test. In reality, they are extremely good surveillance tools and are the only tests that can be used in the long run to understand how widespread the pandemic was.” In the end, he adds, testing needs simply cannot be met by molecular tests alone. As antigen tests start to perform reasonably well, he hopes they will become more widely available, easing the burden on the molecular testing infrastructure.

Sampath believes the FDA’s EUA operates on a “do no harm, but do good” basis. As a result, he thinks it is critical that fast-track tests are adequately monitored and adapted according to the findings. Having witnessed the FDA’s proactive approach to recalling tests when necessary and issuing warnings when performance rates are lower than originally suggested, he is relatively confident in the regulator’s approval process. Still, he’s well aware of the complexity of the agency’s task. “You can’t wait for everything to be in place when, in the meantime, hundreds of thousands of people are getting infected,” he says. “Today, none of the tests that are on the market have gone through a full-blown dossier submission to any of the regulatory agencies.”

Looking ahead, FIND’s testing priority is rapid antigen assays. The organisation is also considering alternative ways to collect and process samples to speed up the evaluation process. Ultimately, Sampath echoes and exemplifies the message of WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus: “test, test, test”. But that’s only a realistic goal because innovation projects like RadX are investing in the development of the range of diagnostics required for the needs of different populations and services. At the helm, Tromberg is cautiously optimistic for the future. After all, he says, “I am representing the thousands of talented people out there working incredibly hard on this, and I’m confident that as an engineering and technology community, we have the capacity to succeed.”